Chapter 1: Welcome

Becoming Neighbours

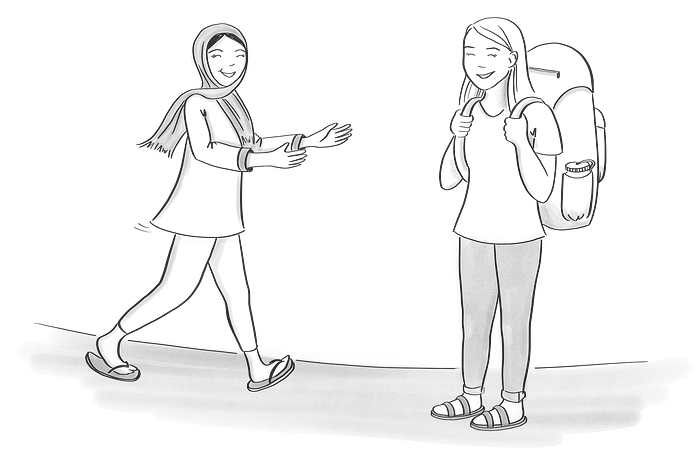

It was early June when Aila welcomed me into my new home at Kinbrace.¹ She must have heard about my arrival, and she came bounding down two flights of stairs from her second-floor apartment and into the backyard. The staircase — which looks out over Vancouver from the east — was veiled in clematis on the brink of bloom.

“Welcome!” she said as she approached me. Her eyes were warm and inquisitive, and her cheeks were flushed with life. A light blue hijab framed her face.

“Thank you,” I said, taking everything in.

I had just returned to Vancouver after nine months of living in France. After finishing my undergraduate degree, I had ventured to Europe to learn French while working as a part-time English teaching assistant at a French lycée in a small town in Normandy.

Aila looked to be about fifteen or sixteen, the same age as my French students, though not one of my students had worn a head covering to class.² If Aila wanted to attend school in France, she would have to check her hijab — this symbol of religious devotion — at the door.

“Welcome to Kinbrace,” she repeated. “You must be Anika!”

And so, upon my arrival at Kinbrace, I found myself being welcomed by a refugee claimant back to the city where I had been born. In the days that followed, I learned that Aila had recently come to Canada herself, leaving her family in Afghanistan at the age of fourteen to follow her older sister, Mahsa, who had already settled in Vancouver. The two of them lived together in a small apartment at Kinbrace. Though this home was temporary, it was home enough, as I would soon learn, for them to produce steaming soup and fresh, round loaves of bread for all their neighbours, including me. Aila’s status was precarious, but she opened her arms to me, and in that first moment, we saw each other plainly as fellow travellers, both ready to be welcomed home.

We are in solidarity

“Welcome” is a greeting that goes both ways. At Kinbrace, welcome begins with the recognition that we are all seeking safety and belonging. From that common ground, we choose to live in solidarity as neighbours.

“Welcome,” says the man and his teenage son who arrived in Canada just last week. “Welcome,” says the woman who has supported refugee claimants with their legal documentation for the past fifteen years. “Welcome,” says the four-year-old boy who lives at Kinbrace with his Canadian family.

We know we are living in solidarity with our refugee claimant neighbours when we make our home together — a home where each of us has a place and a voice to say, “Welcome.”

When we are at our welcoming best, our welcome is not simply a courtesy, but a true invitation into shared life. When we live side by side, people who are experiencing forced displacement are no longer “strangers”; they become neighbours, friends, sisters or brothers, and people with inherent dignity and agency. We know we are living in solidarity with our refugee claimant neighbours when we make our home together — a home where each of us has a place and a voice to say, “Welcome.”

Bearing witness to exile

Our welcome could easily be drowned out in a world of forced displacement. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), there are at least 82.4 million people in the world who have been displaced from their homes. Of these, 48 million are internally displaced and remain within their country; 26.4 million have been forced to leave their countries and are classified as refugees; and 4.1 million are living as refugee claimants or asylum seekers who have yet to gain official refugee status.³ These are numbers I cannot comprehend, especially knowing there is a face, a name, and a story connected to each one. The scale of forced displacement is formidable, and those of us who seek to provide assistance to displaced people need a response that actively resists paralysis. We need not only the word “welcome,” but practices of welcome to live out in daily life.

The Kinbrace value of welcome is lived out when we bear witness to exile up-close and personal, working at the scale of relationships rather than programs. When news headlines and UNHCR statistics make our heads spin, we pull our chairs up to the table and get to know our neighbour. We talk about the things that draw us together. “Do you like to cook?” “Does your name have a special meaning?” “Do you play an instrument?” While we face daunting numbers of newcomers who lack adequate shelter in our city, we respond with homes, not institutions. We choose a form of impact that prioritizes human dignity over numbers. Inevitably, this means that we must say “no” to many in order to say “yes” to some. This is hard, but it’s human. And with 82.4 million people forcibly displaced from their homes, we cannot afford to lose sight of our common humanity.

We live with refugee claimants

We live out this vision of welcome in the middle of a residential block on a busy street in East Vancouver. Kinbrace comprises two houses that contain nine independent apartments between them (six short-term units for refugee claimants and three longer-term units for hosts). Hosts may be Canadians or those who have lived the refugee journey and are on their way to citizenship. Architecturally, the two houses don’t have much in common — one is a hundred-year-old character home and the other is a “Vancouver Special” with all the marks of 1960s modernism — but there is no fence between them. Instead, the wooden posts of the clematis-clad staircase descend into a joint backyard with a spacious shared patio. This paved area is the site of summertime outdoor dinners, lively cricket matches, and a regular after-school parade of scooters, tricycles, and bikes. Beyond the patio there are garden beds, a chicken coop with several chatty hens, and a small patch of lawn bordered by ferns.

Every Tuesday evening throughout the summer, we set up long tables draped with blue cotton tablecloths and surrounded with plastic chairs. When the rains arrive in fall, the meal migrates indoors to a common space where the capacity seems to expand as guests arrive: thirty… forty… fifty. Refugee claimants, Canadian neighbours, Kinbrace staff, and friends of the community gather to eat together. Former residents often return with growing children. Whether we are Canadian citizens or we just crossed the border last week, all of us gather to welcome the newest in our midst.

When was the last time someone welcomed you? How would you describe the experience of being welcomed?

Where do refugees or newcomers live when they arrive in your city? If you don’t know, is there a way you can find out?

Think of your social circles. Who usually hosts and why?

Think of a story of displacement in your family. How far back in your family history do you have to travel to find an immigrant or refugee? Who migrated, and under what circumstances?

¹ All names have been changed to protect the privacy of my former neighbours.

² In French schools, any head covering is considered an “ostentatious religious symbol” under the French policy of laicïté (secularism enshrined in law).

³ UNHCR Global Trends Report, 2020. Another 3.9 million are classified as “Venezuelans displaced abroad.”

⁴ A residential architectural style that is square, squat, and quintessentially Vancouver.

Buy a hardcopy | Donate Now | Contact the Kinbrace community

© 2021 Anika Bauman. All rights reserved.